By Jonathan Kohl

Is the grass always greener on the other side? Like any major life decision, deciding to uproot yourself (and potentially your family) and move from one state to another is not an easy decision. Although laws, taxes and climate are our focus, there could be many more things to think about, depending on your family's needs and desires. Whatever the reason, it is important to have as much information as possible available as to the "why" and the "how" when it comes to leaving one jurisdiction for another.

Katten's recent Private Wealth Seminar addressed change-in-domicile planning and covered five things to think about when making a move.

1) Why move? The current landscape and domicile vs. residency

Before moving, distinguish between state factors and federal standards across jurisdictions. Every US citizen living domestically starts at the same point, with an estate tax exemption of $12.06 million (In 2022 — this number is expected to increase to approximately $12.9 million in 2023, but is set to sunset in 2026 to $5 million, adjusted for inflation). Every dollar you have in your estate over that amount is taxed at a 40 percent rate. Married couples have double this amount and have "portability" options — one spouse's unused exemption can be "ported" over for the other spouse to use.

With the federal framework in mind, consider that each state has its own rules regarding income tax rate and estate tax (exemption amount and rate). For example, Illinois has an estate tax exemption of $4 million and a graduated estate tax rate up to 16 percent. Illinois also has its own flat income tax rate of 4.95 percent. Illinois gets a bad rap tax-wise, but that is more due to the totality of the circumstances. Illinois' income tax rate is actually middling (other notable states: California at 13.3 percent, New York at 10.9 percent, Florida, Texas and Nevada all at 0 percent). The bad reputation likely stems from the fact that Illinois has both its own income tax and an estate tax. The estate tax exemption for Illinois is also middling compared to states that have exemption amounts and/or rates (i.e., Oregon's exemption is $1 million, Washington's is $2.2 million, New York's is $6.1 million), but note that less than half the states have their own estate tax. All states in the south and most in the west do not have a separate estate tax.

Another key consideration in a move across jurisdictions is "residency" and "domicile" and how they differ. "Residency" is more of an objective standard. Residency is, put simply, where you are located. "Domicile" is a more subjective standard. Domicile is the place where you intend to permanently reside until some unexpected event occurs that induces an adoption of a different permanent residence. Once established, domicile remains unchanged until a new domicile is effectively established. Put more broadly, a person can have multiple residences but only one domicile. Both residency and domicile are important when evaluating income tax and estate tax considerations and consequences when leaving one jurisdiction for another.

Moves are triggered by a number of factors, financial and personal. Some may find it desirable to move to a state that has no state income tax and/or state estate tax. Perhaps there are non-financial reasons, such as weather, asset protection (including homestead protection), geography vis-à-vis friends and family and/or best possible access to healthcare. Whatever the reason, having the most information possible and at least a general grasp of the concepts at play are an important starting point.

2) How to move your domicile

How to change your residence is the easy part — just move! Changing domicile can be trickier. Because domicile is entirely based on intent, changing your domicile means you must prove an intent to establish a permanent home in a new state. Several factors may contribute to establishing such an intent. Time matters. To establish a new domicile, a common rule of thumb is that you spend at least six months plus one day in the state in which you intend to establish a new domicile. After a new domicile is established, it is generally recommended you not spend more than six months in any other jurisdiction, although rules may differ by state.

Another easy step to take when changing domicile is to cease claiming a homestead exemption in your former state. First, establish a personal residence in your new state. Although not required, it would be a best practice to consider selling your residence in your former state. Where you claim your homestead exemption is an important factor in demonstrating intent. You only get one bite at the "tax apple." Additionally, file a declaration of domicile in your new state. Not all states have a declaration of domicile form, but for states that do (i.e., Florida), it is such an easy step worth taking.

There is a laundry list of other factors to consider when changing domicile, including:

- the location of your spouse and dependents (although spouses having split-residency can and does happen);

- where you are registered to vote;

- where federal and state income tax returns are filed;

- temporary or permanent nature of work in a given state;

- automobile registration and driver’s license;

- location of professional licenses, healthcare providers and organizational memberships;

- utility usage over time;

- where mail is sent;

- situs of estate planning documents (although a local attorney is not required);

- location of banking and/or safety deposit box; and

- location of burial plot(s).

No one factor is determinative but it is important to remember the burden of proof to establish domicile (or non-domicile) is on the taxpayer. No matter what, keep good records. Record-keeping is critical in proving intent and thus proving domicile (or non-domicile).

3) Income tax considerations when changing domicile

Applying income tax to individuals is relatively straightforward. Illinois applies income tax to the entire net income of an Illinois resident and also the Illinois-sourced income of a non-resident. Illinois presumes Illinois residency if you claim a homestead exemption on Illinois property and/or if you spend more time in Illinois than any other state. Note these presumptions are just presumptions and not determinative of domicile or intent.

Illinois-sourced income for non-residents includes wages from a person and/or organization that transacts business in Illinois, if the services provided are "localized" in Illinois, or, if not localized, then if the business providing the wages has its base of operations in Illinois or the place from which services are directed is located in Illinois. Illinois-sourced income also includes capital gains from the sale of an Illinois asset or rental income from Illinois-sitused real estate. While not an exhaustive list, these are often the most common forms of Illinois-sourced income for non-Illinois residents.

Income taxation of trusts can be more flexible. As a threshold matter, an Illinois trust will pay income tax on its entire income, regardless of the source of said income. An Illinois trust includes (1) a trust created by the will of a decedent who was domiciled in Illinois at death and (2) an irrevocable non-grantor trust of which the grantor was domiciled in Illinois at the time the trust became irrevocable. Note that grantor trusts are taxable to the individual, and would flow accordingly based on the individual income tax rules noted above. The situs of a trust may be dependent on the location of the trustee, other fiduciaries and/or the beneficiaries.

The 2013 Linn casei is the leading case in Illinois regarding the tax situs of a trust. In Linn, an Illinois resident created an inter vivos trust. During this time, the trust was administered by Illinois trustees pursuant to Illinois jurisdiction. Forty-one years after creation of the trust, the trustee distributed all trust property to a new trust in Texas. After assets were distributed to the new trust, there was no non-contingent beneficiary residing in Illinois, no trust fiduciary residing in Illinois, all trust assets were outside Illinois and nowhere in the new trust instrument was Illinois law referenced. The Illinois Department of Revenue attempted to classify the trust as an Illinois resident trust, but an Illinois appellate court agreed with the trustee that the trust was not an Illinois trust. Specifically, the appellate court held that a grantor's residency within a certain state at the time of trust creation was not itself a sufficient connection to satisfy due process in the context of an inter vivos trust. No Illinois cases have addressed this subject since Linn. Notably, Linn emphasizes that the location of the beneficiaries and/or the trustee (or other fiduciary) is important. Documenting the situs and governing law of a trust may be crucial to the determination of where a trust is sitused. Best practices include modifying a trust instrument to remove all citations to a prior jurisdiction.

4) Estate tax considerations when changing domicile

Estate tax as it pertains to individuals is similarly relatively straightforward. Illinois estate tax may be imposed on taxable transfers of property sitused in Illinois. Illinois-sitused property includes all property if the decedent was an Illinois resident at the time of death. If the decedent was a non-resident at the time of death, then transferred Illinois-sitused property includes the real and personal property located in Illinois.

In the estate tax context, trusts may be similar to individuals because a trust can have only one situs, essentially the equivalent of having one domicile. Several factors may be looked to when determining a trust’s situs, including:

- terms of the trust instrument;

- domicile of the Grantor;

- location of the trustee; and

- location of the trust assets.

The terms of the trust instrument can go a long way toward preventing an examination of the other factors. We typically recommend that a trust instrument specify a trust situs, rather than relying on a "floating situs," i.e., the trust situs being "where the trust is being administered." Opting for a "floating situs" opens up the possibility of a more critical examination of the other factors, which may prove more complicated.

Trusts, like people, can change trust situs over time. Importantly, changing trust situs should be done formally. Similar to an individual proving domicile (or non-domicile), documentation helps support the tax position and avoids potential disputes. Changing trust situs can be done in different ways, depending on the state and applicable laws. Changing trust situs is a common objective of nonjudicial settlement agreements (agreement among fiduciaries and beneficiaries pursuant to state law), but can also be accomplished via decanting (distribution from a current trust to a new trust with more desirable terms) or a trustee power granted by the trust instrument and/or state law.

Differences in trust situs are important not only from an income tax and estate tax perspective, but for other trust administration rules as well. This includes accounting rules, fiduciary responsibilities, directed trust provisions, the rule against perpetuities and asset protection.

5) Planning your move: Irrevocable non-grantor trusts

Irrevocable non-grantor trusts (INGs) present a unique opportunity for income tax. The goal of an ING is to shift income away from a high-income tax state to a zero-tax state. For example, a California resident (13.3 percent income tax rate) could establish a Nevada ING (or NING), which has a no state income tax. As the name says, an ING is a non-grantor trust — this ensures that trust income is not taxed by the grantor's home state. Recall that a grantor trust taxes income directly to the grantor, which would derail this strategy before it even became useful. Note: INGs do not prevent the grantor's home state from taxing "source" income for assets sitused in the home state.

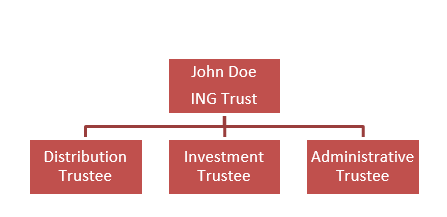

An ING is also an incomplete gift trust, which allowed the trust to be funded without gift tax implications. However, trust assets will be included in the grantor’s gross estate for federal estate tax purposes. This illustrates that the use of INGs is an income tax-based strategy, not an estate tax-based strategy. Additionally, an ING is structured as an asset protection trust, which prevents the trust from being invaded by creditors. The asset protection trust element is also necessary to avoid grantor trust status. When using INGs, a good estate planner must be cognizant to "thread the needle" which is Section 677 of the Internal Revenue Code. Section 677 of the code provides that if the grantor or the grantor's spouse can receive distributions of income from a trust, then the trust is deemed a grantor trust. The ING, however, falls within an exception to Section 677, which provides that the grantor and/or the grantor's spouse may receive distributions of income without the trust being deemed a grantor trust if a distribution of income requires the consent an "adverse party" (i.e., another beneficiary). A common method to thread this needle is to bifurcate the fiduciary roles, for example, into a "Distribution Trustee" an "Investment Trustee" and an "Administrative Trustee."

Consider "Joe." He's a California resident and has a $10 million portfolio of low-basis stock ($1 million). If Joe does no planning and sells his entire portfolio, Joe will realize $9 million in long-term capital gain and be taxed as follows:

- California income tax (13.3 percent) = $1.2 million

- Federal long-term capital gains tax = $2.2 million

- Combined tax = $3.4 million

- Effective blended Federal/state tax rate = 38 percent

Now suppose Joe makes an incomplete gift to a NING and the NING thereafter sells the entire portfolio. The tax consequences are as follows:

- California Income tax (13.3 percent) = $0 à Trust has no California nexus

- Nevada Income tax (0 percent) = $0 à Nevada has no state income tax

- Federal long-term capital gains tax = $2.2 million

- Combined tax = $2.2 million

- Effective blended federal/state tax rate = 23.8 percent

The use of the NING in this example saved the client $1.2 million.

Outside counsel will have these tools and more to help you with your estate planning needs, whether it involves change of domicile planning, income tax planning, estate tax planning or otherwise.