A jury awarded Apple more than $1 billion in damages after finding that smartphones sold by Samsung diluted Apple's trade dress and infringed Apple's design and utility patents. After a partial retrial limited to determining the appropriate amount of damages, Apple still arose victorious with a $930 million award. Samsung moved for judgment as a matter of law and for a new trial. The district court denied those motions, and Samsung appealed. On May 18, 2015, the Federal Circuit upheld the jury's verdict of design and utility patent infringement, but reversed the finding of trade dress dilution.

Trade Dress Claims

At issue on appeal was whether Apple's purported registered and unregistered trade dress associated with its iPhone 3G and 3GS products is functional. Because trademark law gives the trademark owner a "perpetual monopoly," a design that is functional cannot serve as protectable trade dress. Apple Inc. v. Samsung Elecs. Co., Ltd., No. 14-1335, slip op. at 7 (Fed. Cir. May 18, 2015). The standard is even higher when the owner claims trade dress protection over the configuration of a product, as opposed to product packaging or other forms of trade dress. Slip op. at 8. In fact, the court noted that Apple had not cited a single Ninth Circuit case finding trade dress of a product configuration to be non-functional. Id.

Apple claimed the following elements as its unregistered trade dress:

- a rectangular product with four evenly rounded corners;

- a flat, clear surface covering the front of the product;

- a display screen under the clear surface;

- substantial black borders above and below the display screen and narrower black borders on either side of the screen; and

- when the device is on, a row of small dots on the display screen, a matrix of colorful square icons with evenly rounded corners within the display screen, and an unchanging bottom dock of colorful square icons with evenly rounded corners set off from the display's other icons.

Slip op. at 9. "In general terms, a product feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article." Id. (quoting Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 850 n.10 (1982)). Because this case came to the Federal Circuit on appeal from a district court sitting in the Ninth Circuit, the Federal Circuit applied the Ninth Circuit's Disc Golf test for determining whether a design is functional. Under that test, courts consider whether: (1) the design yields a utilitarian advantage; (2) alternative designs are available; (3) advertising touts the utilitarian advantages of the design; and (4) the particular design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture. Slip op. at 10. Because this purported trade dress was not registered, Apple had the burden to prove its validity, which required Apple to show that the product features at issue "serve[] no purpose other than identification." Id. (citing Disc Golf Assoc., Inc. v. Champion Discs, 158 F.3d 1002, 1007 (9th Cir. 1998)). The court of appeals applied those factors and found extensive evidence supporting Samsung's claim that the alleged trade dress was functional. Slip op. at 12–14.

In addition to the unregistered product configuration discussed above, Apple also asserted a claim based on US Registration 3,470,983, which covered the design details in each of the 16 icons on the iPhone's home screen framed by the iPhone's rounded-rectangular shape with silver edges and a black background. Slip op. at 15. Although Apple enjoyed an evidentiary presumption of validity for its registered trade dress, the court again looked to the Disc Golf factors and found that Samsung met its burden of overcoming that presumption and proving the trade dress was functional and the registration invalid. Slip op. at 16. Because the court held Apple's purported trade dress was functional, it vacated the jury's verdict on Apple's claims for trade dress dilution and remanded that portion of the case for further proceedings. Slip op. at 17.

Design Patent Claims

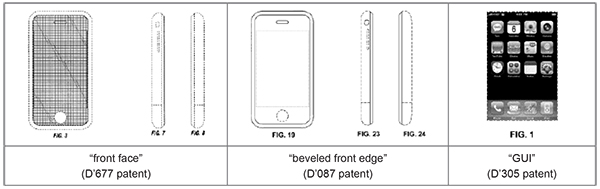

Apple fared better on its design patent claims. Here, Apple asserted three design patents directed to the "front face" (D'677 patent), "beveled front edge" (D'087 patent) and "graphical user interface (GUI)" (D'305 patent) of its iPhone products.

Samsung challenged the court's claim construction and jury instructions for failing to "ignore[]" functional elements of the designs from the claim scope, such as rectangular form and rounded corners. Slip op. at 20. The court disagreed, finding that Samsung's proposed rule to eliminate entire elements from the scope of design claims was unsupported by precedent. Id. Rather, the court found that both the claim construction and jury instructions properly focused the infringement analysis on the overall appearance of the claimed design. Id. at 21.

This victory was financially significant for Apple, as the court found they were entitled to Samsung's entire profits on its infringing smartphones as damages. Like the district court, the court of appeals found that 35 U.S.C. § 289 explicitly authorizes the award of total profit from the article of manufacture bearing the patented design, rather than an apportionment of damages based only on the infringing aspects of the device (i.e., external features and not internal hardware/software). The court of appeals interpreted Samsung's argument as imposing an "apportionment" requirement on Apple—a requirement the Federal Circuit previously rejected in Nike, Inc. v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 138 F.3d 1437, 1441 (Fed. Cir. 1998). Thus, Apple maintains a claim to at least a significant portion of the $930 million damages award in the case.

Summary and Takeaways

Ultimately, after holding that Apple's purported trade dress covering elements of the iPhone's overall shape, black-bordered display screen, and matrix of colorful square icons was invalid, the district court upheld the jury's verdict that Samsung's devices infringed Apple's design patents relating to the iPhone's overall shape, display screen, and matrix of colorful square icons. The image depicted in Apple's now-invalid trade dress registration is below on the left. Figures from two of its still-valid design patents are on the right. Although the overlap in what was claimed in these different forms of intellectual property is readily apparent, Apple lost on one set of claims and prevailed on the other.

.jpg)

It remains to be seen how damages associated with the design patent claims differ from damages associated with the now-invalid trade dress claims. But this much is clear: the Federal Circuit has given a reason for companies to reevaluate the role of design patents in their intellectual property portfolios. The time and expense associated with obtaining design patents will not suit all products, but for the right product, they can provide a valuable method of recovery in litigation involving similar product designs.